Muncy, Pennsylvania

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

Muncy, Pennsylvania | |

|---|---|

Downtown Muncy | |

Location of Muncy in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania | |

Map of Pennsylvania highlighting Lycoming County | |

| Coordinates: 41°12′7″N 76°47′11″W / 41.20194°N 76.78639°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Lycoming |

| Settled | 1797 |

| Incorporated | 1826 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jon Ort |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.84 sq mi (2.19 km2) |

| • Land | 0.84 sq mi (2.19 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 499 ft (152 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 2,440 |

| • Density | 2,891.00/sq mi (1,116.38/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 17756 |

| Area code | 570 |

| FIPS code | 42-52264[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1213993[2] |

| Website | muncyboro |

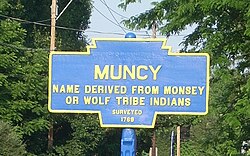

Muncy is a borough in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania, United States. The name Muncy comes from the Munsee Indians who once lived in the area.[5] The population was 2,442 at the 2020 census.[6] It is part of the Williamsport, Pennsylvania, Metropolitan Statistical Area. Muncy is located on the West Branch Susquehanna River, just south of the confluence of Muncy Creek with the river. Currently the borough president is Bill Scott and the mayor is Jon Ort.

History

[edit]Early settlement

[edit]

18th century

[edit]About 1787, four brothers Silas, William, Benjamin, and Isaac McCarty, came here from Bucks County. They were of Quaker extraction. William and Benjamin bought 300 acres (120 ha) known as the "John Brady farm."

John Brady was one of the earliest settlers in the area. He received a land grant which was awarded to the officers who served in the Bouquet Expedition. He chose land west of present-day Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. He built a private stockade on this land in the Spring of 1776, close to present day Muncy, Pennsylvania, which he called "Fort Brady." John Brady's Muncy house was large for its day. He dug a 4-foot-deep (1.2 m) trench around it and emplaced upright logs in that trench side by side all the way around. He filled the trench with dirt and packed the dirt against the logs to hold the log wall solidly in place. This log wall ran about twelve feet high from the ground. He then held this wall in place upright by pinning smaller logs across its top, to keep the wall face steady and solid. The John Brady homestead was perilously close to the leading edge of the frontier of that time, the Susquehanna River. The other side of the Susquehanna was fiercely dominated by the Indians. The Indians resisted settler encroachment on their territory by routinely crossing the Susquehanna to raid the settlers. The settlers just as routinely crossed the Susquehanna to pursue the raiding war parties to retaliate and sometimes to rescue captives taken by the Indians during these raids. In this ongoing skirmishing, both sides committed unspeakable atrocities on the other, which drove a long-lasting cycle of revenge for revenge brutalities between the settlers and Indians. It was in the midst of this extreme danger and violence that Major John Brady chose to settle his family, which set the stage for what happened to him and for what so greatly impacted and influenced his family—especially, his sons, Continental Army Captain Samuel Brady of Brady's Leap fame and Hugh Brady, who became a Major General in the United States Army.

The McCarty brothers divided up the former Brady land, with William taking the portion between what is now West Water Street and Muncy Creek, and Benjamin that portion between West Water Street and the southern boundary. Main Street now represents what was then the boundary between the Brady farm and Isaac Walton's.

In 1797, ten years after coming to Muncy, Benjamin McCarty conceived the idea of starting a town, and began laying out lots on what is now Main Street, and sold them to different parties. His example was followed by his brother William, north of Water street, and by Isaac Walton. The town was named Pennsborough in honor of the William Penn.

19th century

[edit]The town grew slowly and was nothing but a village for many years. More than a quarter of a century passed before an act of incorporation was applied for. Finally, by act approved March 15, 1826, it was incorporated as a borough.

On January 19, 1827, with a population of less than 600, the name was changed from Pennsborough to Muncy. This was done because many persons thought it was "too flat and long," and the new name would be more in accordance with the historical associations of the place, and serve to perpetuate the name of the tribe that first dwelt there, a tribe of Lenape, named Monseys.

One of the common misconceptions about United States history prior to the Civil War is that all the citizens of the northern states were against slavery.[7] In fact many of the "Yankees", were all for slavery, especially in states closer to the Confederacy like Pennsylvania, Ohio and Delaware. There were more than a few abolitionists in Pennsylvania, and Enos Hawley, a Quaker citizen of Muncy, was one of the most prominent abolitionists in Lycoming County. Hawley, a tanner by trade, was, like most Quakers, a strong supporter of the abolition of slavery.[7] Hawley invited a now unknown speaker to come to Muncy to speak against slavery. This speaker arrived in April 1842. His arrival and resultant speech set off a tremendous riot that led to the near destruction of a local schoolhouse and the controversial pardoning of the rioters by Pennsylvania Governor David R. Porter.

The anti-slavery speaker gave his speech at a one-room school in Muncy in April 1842. During the course of the speech, eighteen men gathered outside the schoolhouse. They began throwing rocks and other debris at the school, breaking all of the windows.[7] Enos Hawley and the guest speaker were both injured in the assault. Upon fleeing the school, the abolitionists were pelted with eggs. The rioters followed Hawley and his guest to Hawley's home at the corner of High and Main Streets. They continued the assault on Hawley's home until after midnight, when the local law enforcement officers were able to quell the riot and arrest the rioters.[8] The rioters were indicted in September and went to trial in October, when thirteen of the eighteen rioters were found guilty as charged. The jury's deliberation was quite a long process.[7]

Abraham Updegraff was a member of the jury who was the driving force that led to the conviction of the rioters. Updegraff, an ardent abolitionist who was a vital member of the Underground Railroad in Lycoming County, was able to convince his peers that the rioters deserved to be punished. The first jury vote was 11 to 1 in favor of acquittal, with Updegraff being the lone dissenter. Updegraff argued that "we have been sworn to try this case according to the law and the evidence presented and that if no contradictory evidence [is] offered by the defendants than we could do nothing more than to convict them." He was able to make his argument in German which was the native tongue of three other jurors. The second vote was 9 to 3 in favor of acquittal. A third vote brought about the conviction of 13 of the 18 men charged in the Muncy Abolition Riot of 1842. This conviction was essentially overturned by Governor David R. Porter when he pardoned the rioters several days later. Governor Porter's statement of pardon said, "It is represented to me by highly respected citizens of Lycoming County, that this prosecution was instituted more with a view to the accomplishment of political ends than to serve the cause of law and order."

Porter's pardon message placed the blame for the riot on the abolitionist speaker. Porter stated that the speech was "notoriously offensive to the minds of those to whom they were addressed and were calculated to bring about a breach of the peace."[7] This pardon led to Governor Porter being given the less than flattering nickname of the "Previous Pardonin Porter."[8] Historians believe that Porter pardoned the rioters under political pressure that was rampant, in the years prior to the Civil War, regarding the issue of slavery.

21st century

[edit]Muncy has nearly 2,700 residents. Its high school football team and the Montgomery high school team play annually for The Shoe, a trophy created in 1961 from an old athletic shoe found in the Muncy High School locker room; the shoe has since been bronzed and mounted on a wooden box. Muncy currently leads the series with 28 wins to Montgomery's 18. Hughesville's high school team and Muncy are also rivals. In the first game of the season, September 4, 2010, Muncy kept The Shoe by shutting out Montgomery 52–0. As of December 2017, Muncy still is in possession of The Shoe.

The Muncy Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[9]

Geography

[edit]

Muncy is located at 41°12′7″N 76°47′11″W / 41.20194°N 76.78639°W (41.201969, -76.786333). Lycoming County is approximately 130 miles (209 km) northwest of Philadelphia and 165 miles (266 km) east-northeast of Pittsburgh. Muncy is surrounded by Muncy Creek Township.[10]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough has a total area of 0.8 square miles (2.1 km2), all land. It has a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) and average monthly temperatures range from 26.8 °F in January to 72.3 °F in July. [1] The hardiness zone is 6b.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 901 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,010 | 12.1% | |

| 1870 | 1,040 | 3.0% | |

| 1880 | 1,174 | 12.9% | |

| 1890 | 1,295 | 10.3% | |

| 1900 | 1,934 | 49.3% | |

| 1910 | 1,904 | −1.6% | |

| 1920 | 2,054 | 7.9% | |

| 1930 | 2,413 | 17.5% | |

| 1940 | 2,606 | 8.0% | |

| 1950 | 2,756 | 5.8% | |

| 1960 | 2,830 | 2.7% | |

| 1970 | 2,872 | 1.5% | |

| 1980 | 2,700 | −6.0% | |

| 1990 | 2,702 | 0.1% | |

| 2000 | 2,663 | −1.4% | |

| 2010 | 2,477 | −7.0% | |

| 2020 | 2,442 | −1.4% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 2,425 | [6] | −0.7% |

| Sources:[11][4][12][3] | |||

As of the 2000 census,[4] there were 2,663 people, 1,142 households, and 749 families residing in the borough. The population density was 3,174.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,225.6/km2). There were 1,233 housing units at an average density of 1,469.7 per square mile (567.5/km2). The racial makeup of the borough was 98.46% White, 0.04% African American, 0.08% Native American, 0.23% Asian, 0.30% from other races, and 0.90% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.94% of the population.

There were 1,142 households, out of which 28.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.8% were married couples living together, 8.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.4% were non-families. 29.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33 and the average family size was 2.86.

In the borough, the population was spread out, with 23.5% under the age of 18, 7.2% from 18 to 24, 28.3% from 25 to 44, 23.7% from 45 to 64, and 17.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.9 males.

The median income for a household in the borough was $33,603, and the median income for a family was $38,934. Males had a median income of $31,900 versus $22,222 for females. The per capita income for the borough was $17,782. About 8.3% of families and 10.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.0% of those under age 18 and 3.1% of those age 65 or over.

Government and infrastructure

[edit]The United States Postal Service operates the Muncy Post Office.[13]

The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections State Correctional Institution - Muncy is located in Clinton Township, Lycoming County, near Muncy.[14] SCI Muncy has Pennsylvania's death row for women.[15]

Notable people

[edit]- Anna Morris Holstein (1824-1901), organizational founder, civil war nurse, author[16]

- Ed Ott, (1951-2024), former Major League Baseball player

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Manhattan to Minisink: American Indian Place Names of Greater New York and Vicinity ISBN 978-0-806-14336-1 p. 4

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". Census.gov. US Census Bureau. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Lou Hunsinger Jr. "Lycoming Remembers Muncy Abolition Riot". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "Riots, Rumors and Stories: The Underground Railroad Period in Pennsylvania's Heartland" (PDF). Pennsylvania Heartland Humanities Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "2007 General Highway Map Lycoming County Pennsylvania" (PDF) (Map). 1:65,000. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. Retrieved December 27, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Post Office Location - MUNCY Archived June 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on August 24, 2010.

- ^ "Directions to SCI Muncy." Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. Retrieved on August 24, 2010.

- ^ "Death Penalty FAQ." Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. 2 (2/4). Retrieved on July 26, 2010.

- ^ Biddle, Gertrude Bosler; Lowrie, Sarah Dickson (1942). "Anna Morris Holstein 1824-1900". Notable Women of Pennsylvania. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-598-57495-4.